I Built A Mac App In Three Hours Without Writing Code

And you can too.

I opened Visual Studio Code at 2pm yesterday.

Never built a Mac app before.

Never written Swift.

Never touched Xcode beyond opening it once and immediately closing it because what the fuck is happening in there.

By 5pm, I had a fully functioning voice transcription app running on my computer.

Not a prototype.

Not a proof of concept.

A real app that I’m actually using right now to write this.

It transcribes my voice almost instantly using local AI models, removes filler words, cleans up mistakes, and activates with a single hotkey.

No $15/month subscription.

No sending audio to cloud APIs.

No waiting for servers to respond.

Just me, an idea, and an AI that understood what I was trying to build.

The Subscription That Became A Problem

I’ve been paying for WisprFlow for months.

It’s a simple tool.

You press a hotkey, speak into your mic, and it transcribes your words with better accuracy than standard voice-to-text.

Then it pastes the result wherever your cursor is sitting.

Does exactly what it says.

Costs $15 a month.

The problem wasn’t the price.

The problem was the friction.

Every time I used it, there was this delay.

Not massive, but noticeable.

That half-second pause where you’re waiting for your audio to travel to OpenAI’s Whisper API, get processed, and come back.

Sometimes it took longer.

Sometimes it just failed and I’d have to try again.

And I kept thinking - this is such a simple function.

Press button, transcribe audio, paste text.

Why does this need to ping a server halfway across the internet?

Local AI models exist.

They’re free.

They run on my laptop.

So why the hell was I paying $15 a month and dealing with latency for something my computer could do instantly?

I wasn’t the only one annoyed by this.

But most people in that position have two options.

Keep paying and deal with it, try and find an alternative app (that probably doesn’t work the way they want it to) or learn to code and spend weeks figuring out Mac app development.

I had a third option.

Ralph Wiggum And The Loop That Never Stops

Twitter’s been buzzing about something called the Ralph Wiggum method.

For anyone who hasn’t watched The Simpsons - and you should have - Ralph Wiggum is the kid who’s perpetually confused.

You tell him something and he just resets back to whatever he was thinking before.

Turns out that’s a feature, not a bug, when it comes to AI coding.

The Ralph Wiggum method works like this.

You give Claude Code a prompt describing what you want to build, then you run it in a loop.

The AI attempts to build the thing.

It checks its work.

It finds problems.

Then instead of exiting, a Stop hook blocks the exit and feeds the same prompt back in.

The files it just changed are still there, so each iteration builds on the last.

You cap the loop with a max iteration count and a completion phrase that Claude must output only when the task is truly done.

It’s iterative development on steroids.

But it works best when success is verifiable.

Tests pass, lint is clean, build succeeds.

If the prompt is fuzzy, it tends to wander.

Most people using AI to code hit a wall around the third or fourth iteration.

The context gets muddy.

The AI starts making weird decisions based on half-remembered earlier choices.

Things break in cascading ways.

Ralph resets that.

Every iteration starts with clarity:

This is what we’re building

This is where we are

This is what needs to happen next

I’d been playing with Claude Code on some web projects.

Mostly small stuff - HTML, React, things that felt safe and familiar even though I’m not a developer.

But I’d never built a real application.

Something that runs natively on macOS, has proper UI, handles system-level permissions.

That felt like a different category entirely.

But I’d just installed Droid, which is basically a wrapper that gives Claude more context and better memory.

And it had this Ralph Wiggum skill built in.

Fuck it.

Let’s try.

From Product Brief To Five Agents Building In Parallel

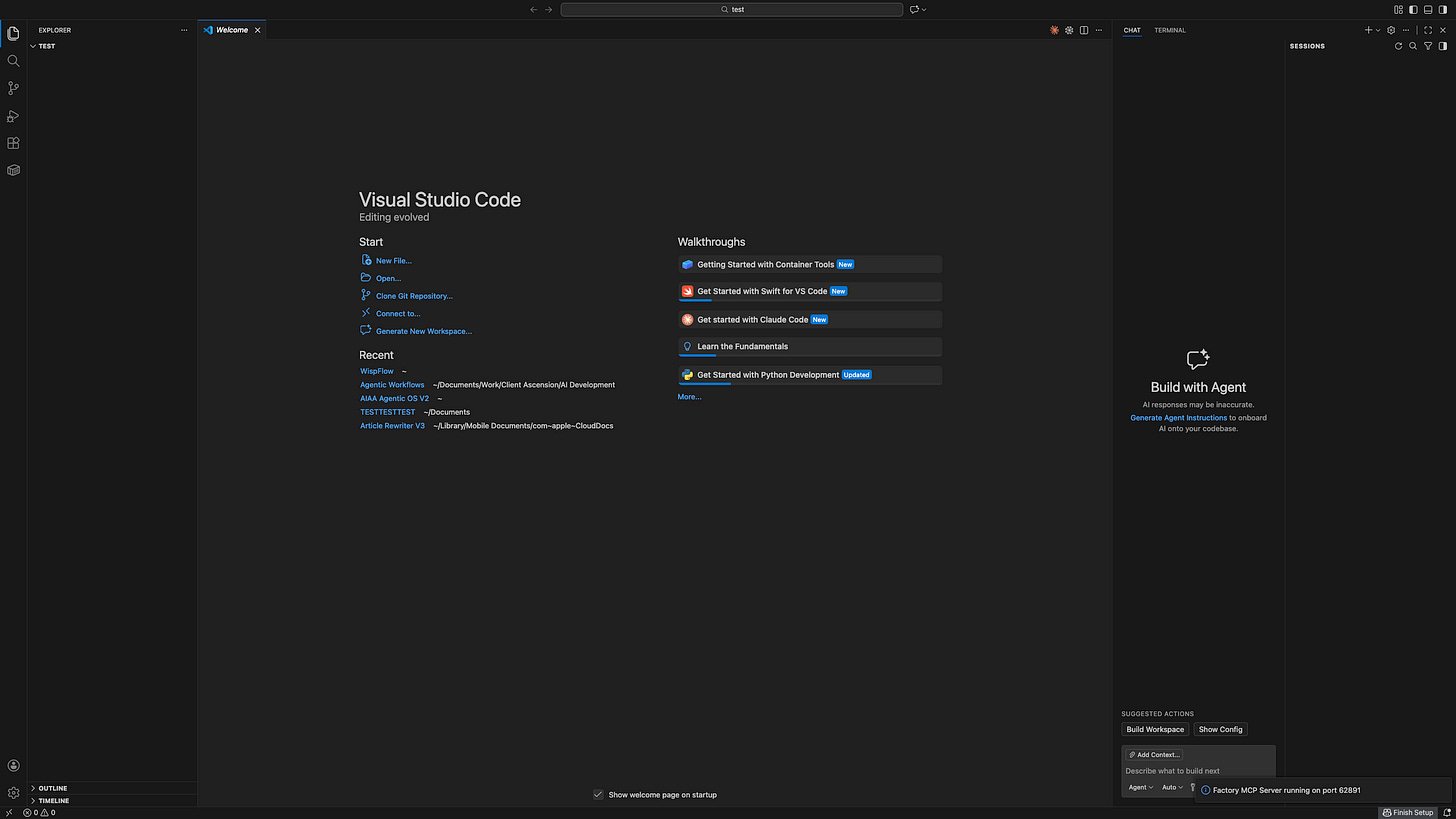

I opened a new project in Visual Studio Code.

For those that don’t know, this is what’s called an IDE and it’s an app used to develop software.

This is what it looks like when you start:

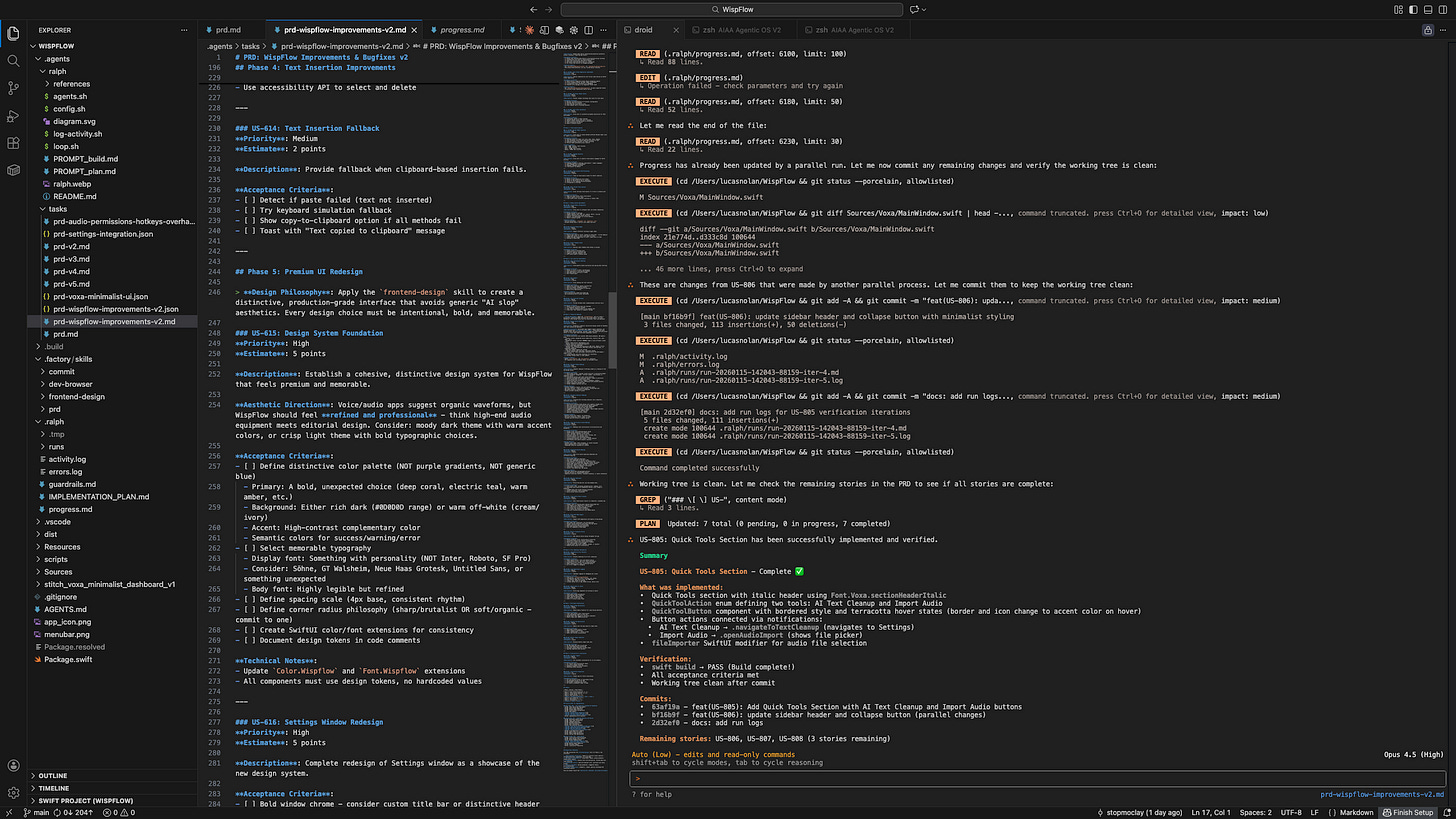

This is what it looked like when I was done:

Scary as hell right?

But I started like the first image.

Blank slate.

No boilerplate.

No starter template.

First step - create a PRD.

Product requirements document.

I didn’t write it myself.

I told Claude what I was building.

A WisprFlow replacement that runs locally, transcribes fast, removes filler words, activates with a hotkey - and let it generate the requirements.

It came back with a clean spec.

Broken into features, prioritized, clear acceptance criteria for each piece.

Then I initialized the Ralph method.

Five agents.

Each running the iteration loop ten times.

They split up the work - one handling the UI, another working on the audio capture pipeline, another integrating the local Whisper model, another dealing with hotkey registration and system permissions.

I hit run and watched the terminal start spitting out activity.

File created.

Function defined.

Test passed.

Commit pushed.

File created.

Error caught.

Fixed.

Test passed.

Commit pushed.

It was like watching a construction crew work on five different parts of a building simultaneously.

Occasionally they’d coordinate - the UI agent would need to know what functions the audio agent had created, the hotkey agent would need to hook into the transcription pipeline.

Mostly, though, they just kept iterating.

I grabbed coffee.

Checked my phone.

Came back fifteen minutes later and the structure was already there.

Basic app shell, audio input working, transcription pipeline roughed in.

Another twenty minutes and it was cleaning up edge cases.

What happens if the mic permission isn’t granted?

What if the model fails to load?

What if someone presses the hotkey twice rapidly?

The weirdest part - I barely touched the code.

I’d glance at what was being built, make sure it aligned with what I wanted, occasionally clarify something in the PRD when an agent seemed confused.

But I didn’t write functions.

Didn’t debug syntax errors.

Didn’t spend three hours figuring out how to register a global hotkey in Swift.

The AI did that.

When Understanding Beats Skill

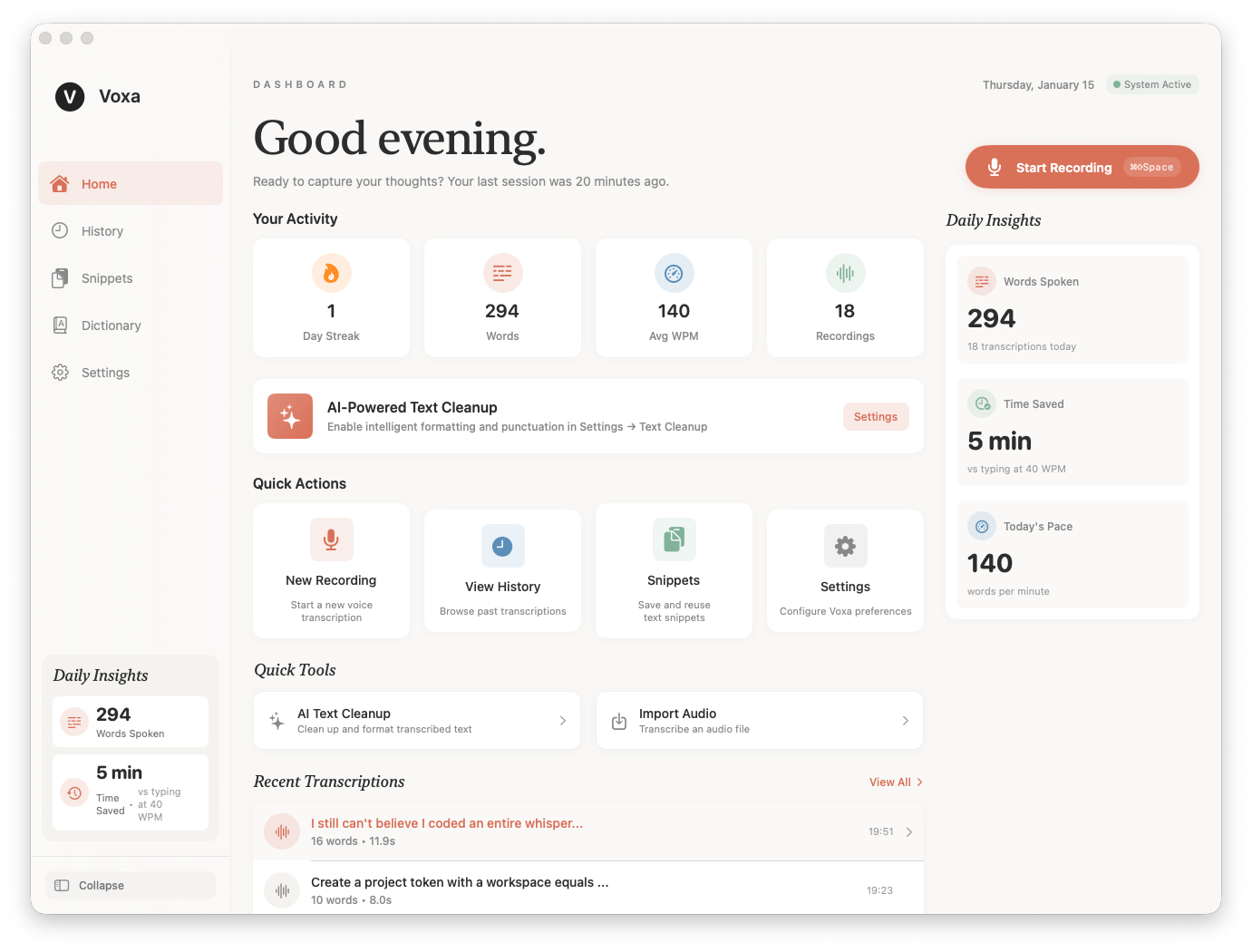

By hour three, I had Voxa running.

I pressed my hotkey, spoke into the mic, and watched text appear instantly where my cursor was sitting.

No delay.

No server round trip.

Just immediate transcription using a local Whisper model.

It felt like magic in that specific way that technology feels like magic when it finally works the way it should have worked all along.

The app looked beautiful too, check it out:

And I kept thinking…

I didn’t know how to do this three hours ago.

I still don’t know how to do this, in the traditional sense.

If you asked me to explain the codebase line by line, I’d struggle.

If you asked me to build this from scratch without AI, I’d have no idea where to start.

But I understood what I wanted.

I understood the problem I was solving.

And I understood enough about how the pieces fit together to guide the AI when it got stuck.

That was enough.

This is the thing people miss about AI development tools.

They’re not replacing developers.

They’re changing what “being a developer” means.

The moat used to be technical skill.

Knowing syntax.

Understanding frameworks.

Having the patience to debug cryptic error messages for hours.

Now the moat is understanding.

Knowing what problem you’re solving, knowing enough about the solution space to guide the AI, and having the persistence to iterate until it works.

I’ve seen actual developers struggle with AI coding tools because they keep trying to wrestle control back.

They see the AI make a choice they wouldn’t have made and immediately jump in to correct it, breaking the iteration flow.

Meanwhile, non-developers approach it as a collaboration.

“Here’s what I want, here’s the feedback on what you built, let’s try again.”

And these guys end up shipping things that would’ve taken them months to learn to build themselves.

The Future Looks Different From Here

I’m going to sign Voxa with my Apple developer account later today.

Claude’s going to do that part too, because I sure as hell don’t know the code-signing process.

Then I’m giving it away.

But only to people in my community.

AIAA, Client Ascension members, and Applied Leverage subscribers.

The people who’ll actually appreciate what this represents.

Not because the app itself is revolutionary.

WisprFlow already exists.

There are probably other local alternatives.

But because this is proof.

Proof that you don’t need to make do with the solutions that exist.

Proof that you can build your own tools when the available options have friction you don’t want to tolerate.

Proof that technical skill is no longer the bottleneck for creation.

The bottleneck is now whether you can clearly articulate what you want and persist through the iteration cycles until it works.

I started seeing this shift a few months ago.

People building functional web apps who’d never written code.

Designers creating their own prototyping tools.

Writers automating complex publishing workflows.

But building a full Mac application in three hours pushed it into a different category for me.

We’re crossing into territory where the question isn’t “can this be built?” but “can you describe what you want clearly enough for an AI to build it?”

And if you can’t describe it clearly, that’s not a technical problem.

That’s a thinking problem.

Most people have the thinking part.

They know their pain points.

They know what would make their workflow better.

They just never learned to translate that knowledge into code.

Now they don’t have to.

You just need to:

Understand the problem well enough to explain it

Understand the solution space well enough to evaluate what gets built

And care enough to keep iterating until it works

That’s it.

Technical skill is becoming commodified.

Understanding and persistence are becoming the differentiators.

Start where you are.

Solve the problem in front of you.

Build the solution that doesn’t exist yet.

The tools are there.

The models are free.

The only question is whether you’re willing to try.