Single-Serving Friends

A case for talking to strangers

Have you ever seen the film Fight Club?

One of my favourites, based on the fantastic book by an author I love, Chuck Palahniuk.

If you haven’t seen it, there’s a scene near the beginning that always stuck with me.

In the film, our unnamed protagonist worked as a recall coordinator for a major car company.

His job was to attend accident sites and calculate whether paying out lawsuits for dead customers cost more than issuing a recall.

A times B times C equals X.

If X is less than the cost of a recall, they don't do one.

He lived in hotels.

Ate airline food.

Existed in perpetual transit between crashes.

And somewhere over Nebraska or Tennessee, he coined a term that I’ll always remember:

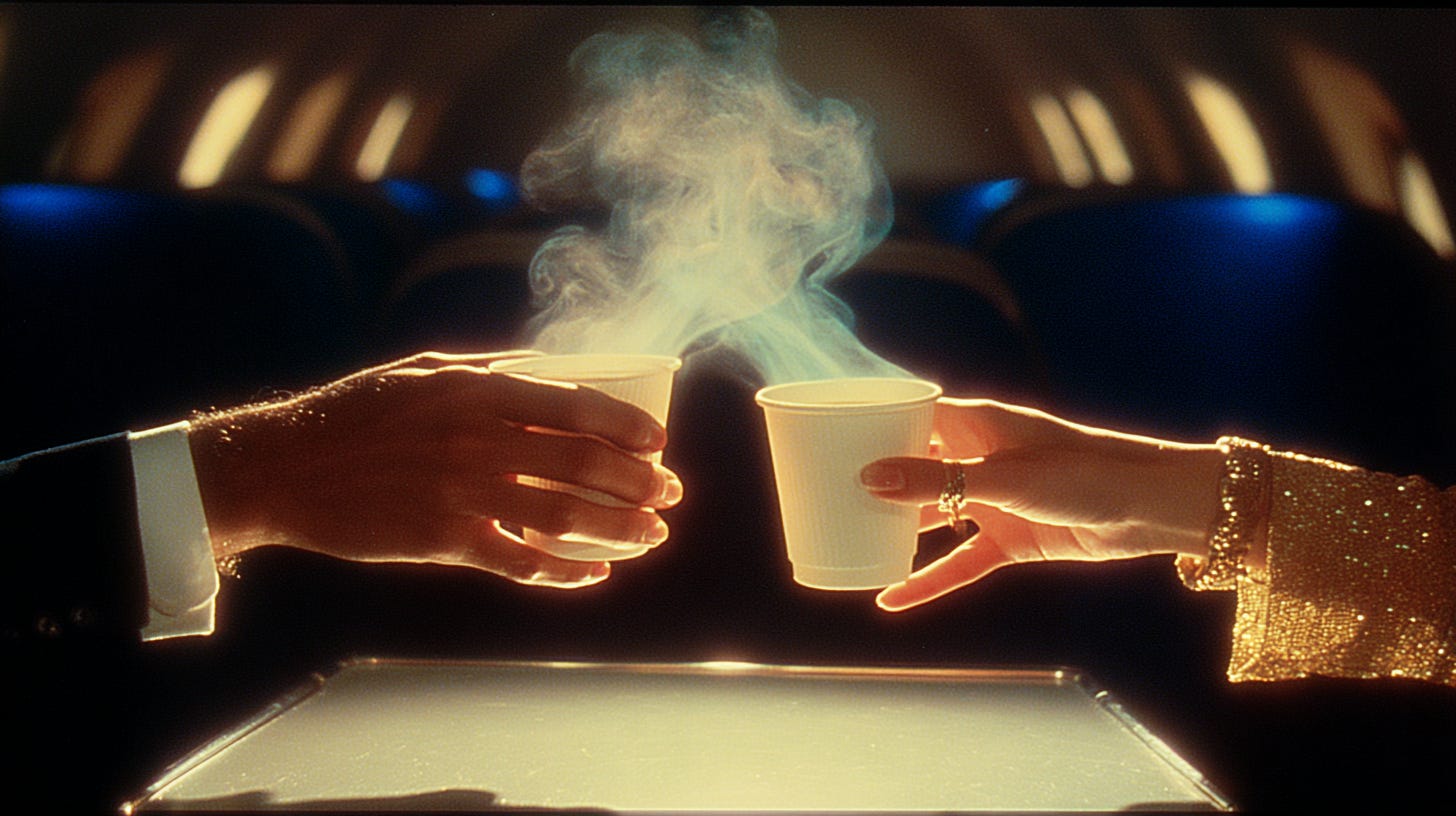

Single-Serving Friends.

"Everything on a plane is single-serving," he said. "Even the people."

Single-serving sugar

Single-serving cream

Single pat of butter

Shampoo-conditioner combos

Sample-packaged mouthwash

Tiny bars of soap

The people you meet on each flight? Single-serving friends.

Once you realise that, there’s a weird freedom that takes hold.

The guy in 18B will never know your last name.

The businesswoman in 12A will forget this conversation before her Uber arrives.

We're all just passing through each other's lives at 35,000 feet, disposable as the peanuts they don't serve anymore.

But here's what Fight Club’s narrator got backwards.

He saw single-serving as a limitation.

A symptom of his alienation from humanity.

Everything disposable, even people.

What if it's actually permission?

The Math of Having Nothing to Lose

About a year ago I sat next to an older woman on a flight to Newark.

We didn't speak for the first hour.

I had my laptop open, she had a book.

Standard airplane protocol.

Establish your personal bubble, defend it with body language and noise-canceling headphones.

Then the turbulence hit.

Not the bumpy kind, the drop-your-stomach kind.

The flight attendants sat down mid-service.

The woman closed her book.

"I hate flying," she said.

"Most crashes happen during takeoff or landing," I said. "We're past the danger zone."

"That's not actually comforting."

We started talking.

Turns out she was a divorce attorney heading to a conference.

I asked what makes a good divorce attorney.

She said the ability to watch people destroy everything they built together and not take sides.

"You ever want to just tell them they're both being idiots?" I asked.

"Every single day," she said.

Then she told me about a case where a couple spent $40,000 in legal fees fighting over who got the dog.

Neither of them even liked the dog that much.

They just couldn't stand losing to each other.

We talked for two hours.

I learned about her marriage (second, seems good), her kid's anxiety disorder, her theory that most people would rather be right than happy.

She learned about my business, my writing, my belief that most advice is just autobiography with a bow on it.

When we landed, we said it was nice talking.

I don't remember her name.

But I think about that conversation regularly.

Research from Cornell on anonymity and self-disclosure found that people regulate what they share based on who's listening and how much that relationship matters.

We disclose more overall to close friends and family, but we hold back certain high-shame, high-risk topics specifically because those relationships matter.

With strangers, especially anonymous or one-time strangers, the reputational cost approaches zero.

No need to manage long-term impressions.

No risk of them changing how they see you in ways that echo through your life.

The divorce attorney and I had nothing to lose.

Neither of us cared what the other thought of each other.

We'd never see each other again.

Our conversation existed in a bubble that popped the moment we stepped into baggage claim.

That's not a bug.

That's the whole point.

Liminal Space, Real Talk

Planes are weird.

You're literally between places, between versions of your life.

You left home-you at the departure gate.

You haven't arrived at destination-you yet.

For a few hours, you're no one.

Just a body in a seat with the suspension of normal social rules.

Most people treat this like dead time.

Headphones on, laptop out, do not disturb.

I get it.

Airports are exhausting.

Flying is uncomfortable.

The last thing you want is some chatty asshole in the middle seat asking about your weekend.

But here's what you're missing.

That forced proximity creates conversational depth that "let's grab coffee sometime" never achieves.

You have three hours.

Neither of you can leave.

There's no phone to check (well, airplane mode at least).

No other friends to drift toward at a party.

No polite exit strategy.

If the conversation sucks, it's going to be a long flight.

So there's incentive to make it not suck.

And if it's good, you can go deep because, again, what's the downside?

They learn you're struggling with something?

They think you're weird?

You land in 90 minutes and never speak again.

I've had seatmates tell me about detailed family dramas.

Career pivots they're terrified to make.

Kids they're worried about.

Money they lost.

Dreams they gave up on.

Things they likely hadn't told their partners or best friends.

Why me? I'm nobody to them.

Exactly.

Psychological research on self-disclosure has been trying to explain this for decades.

A 1976 study found that people disclose more to friends than strangers overall, which seems to contradict the seatmate phenomenon.

But that study measured typical disclosure across a range of topics in structured settings.

It didn't account for selective disclosure of specific high-stakes material in organic contexts.

What matters isn't the average amount of sharing.

It's what kinds of truths come out, and under what conditions.

Strangers get access to different truths than intimates.

Not necessarily more, but different.

The stuff that feels too risky to voice to people who matter.

The Business Case for Talking to Strangers

Global business travel hit $1.5 trillion in 2024, surpassing pre-pandemic levels.

Companies are paying for people to fly across the country or the world because face-to-face matters.

But most of that value is captured in planned interactions.

The conference

The client meeting

The pitch

Meanwhile, you're spending 4-6 hours in transit treating your seatmate like an obstacle.

I'm not saying every flight is a networking opportunity.

Most seatmates are tired, most conversations go nowhere, and sometimes you just need to close your eyes and survive the flight.

But occasionally, you sit next to someone interesting.

And most people never find out because they never ask.

Two years ago I sat next to a guy who ran logistics for a mid-size e-commerce company.

We started talking about supply chain stuff.

He mentioned a problem they were having with returns processing.

I mentioned a software solution I'd read about.

He asked for the name.

I connected to the airplane WiFi and sent it to him.

Six months later, he sent me an email.

They'd implemented the solution.

Saved them something like $200K annually.

He wanted to know if I consulted.

I don't.

But I connected him with someone who does.

That person made $30K on the engagement.

I made a friend who occasionally sends interesting people my way.

All because I asked what he did for work.

That's not even the best example.

The best example is the woman who’s husband became a client after we talked for three hours about Florida real estate.

Or the founder who gave me a book recommendation that changed how I thought about creative work.

None of these were planned.

None of them came from "networking."

They came from being on a plane with a person and treating them like a person instead of an obstacle between me and my aisle space.

Conferences get credited as the driver of business travel because they're measurable.

A quarter of travel managers cite them as a top growth factor.

60% of business travelers plan conference trips specifically to network.

But nobody tracks the ROI of random seatmate conversations because they're impossible to attribute.

That doesn't mean the value isn't there.

It just means most people leave it unclaimed.

How to Actually Do This Without Being That Guy

Look, there's a wrong way to do this.

The guy who launches into his elevator pitch before you've stowed your bag.

The person who treats every conversation like a sales opportunity.

The LinkedIn bro who opens with "so what do you do?" in a tone that screams "are you worth my time?"

Don't be that person.

The right way is simpler: be curious.

Ask a question because you actually want to know the answer.

"What takes you to Denver?" is fine.

So is "Good book?" or "Business or pleasure?" or literally anything that isn't aggressive or presumptuous.

Then listen.

Not for what you can get from them.

Not for the networking angle.

Just listen because people are interesting when you give them room to be.

You just need a thread, an idea, an experience that you can relate to and open up the conversation.

Some people will one-word you.

That's fine.

They don't want to talk.

Put your headphones back on.

But some people will light up because someone asked.

And then you're in a conversation.

Real one, not a transactional exchange of business cards and bullshit.

You're two humans between places, with nothing to lose and nowhere to be for a few hours.

That's where opportunities lie.

Not every time.

Probably not most times.

But enough times that it's worth taking the shot.

The Narrator Was Half Right

Fight Club’s narrator saw single-serving as emptiness.

Evidence that modern life had turned everything, including human connection, into prepackaged convenience.

Use once, throw away, move on.

He wasn't wrong about the alienation.

He was wrong about the direction.

Single-serving isn't the problem.

It's the solution to a different problem.

The social cost of honesty.

The exhaustion of reputation management.

The weight of being known.

With people who know you, you have to be the person they know you as.

With strangers, you can be anyone.

Including, occasionally, yourself.

The people in your life who matter most will never hear certain things from you.

Not because you don't trust them, but because you trust them too much to risk what that truth might do to how they see you.

The stranger in 12A has no such power.

So sometimes the stranger gets the truth your best friend doesn't.

That's not sad.

That's useful.

Your next flight is a room full of people you'll never see again.

Most of them will stay strangers.

That's fine.

But one of them might be the most interesting conversation you have this month.

One of them might know something you need to know.

One of them might become something you weren't looking for.

You won't know unless you ask.

The narrator thought single-serving friends were evidence of a disposable culture.

What they actually are is lottery tickets.

Most people won't scratch them.

You should.